Collaboration is like a muscle: the more you use it, the stronger it gets. And research is clear that organizations and teams with a collaborative culture feel better and produce more. So, how do you create and strengthen a collaborative culture?

In a recent visit to the Gladstone Institutes headquarters in San Francisco, I spoke with some of the Gladstone leadership team about the relationship between their collaborative culture and their promising breakthroughs in the fight against unresolved diseases including SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). With over 350 world-class scientists and researchers, including two Nobel Prize winners, Gladstone Institutes was perfectly poised at the onset of the pandemic to turn its innovative research with other viruses such as HIV to understand and treat COVID-19 and its variants. Based on Gladstone’s experience and APQC research, here are three approaches you can take to build and sustain a collaborative culture.

1. Hire, reward and celebrate the behaviors you want

Hire collaborative people. Gladstone leaders seek out people whose collaborative skills and attitude have been demonstrated in prior jobs and scientific pursuits. “People in the research community know each other and can find out what it was like to work with someone. Were they a prima donna or a key player in a team effort?” explained Melanie Ott, MD, PhD. and Director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology.

Gladstone follows with careful interviewing to identify scientific excellence and a rare commodity: the willingness to take research risks in pursuit of breakthrough science and treatments. Gladstone’s vision is to overcome unsolved diseases through transformative biomedical research. However, this is not the low-hanging fruit of research and there is no guarantee of success. “Academic researchers are not known as being risk takers—the system doesn’t reward it. So we have to find the best people who are also willing to do riskier research and make sure they feel supported and encouraged,” said Katherine Pollard, PhD. and Director of the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology.

Reward, promote and celebrate collaborative behaviors. Have lots of ways to recognize achievement and the behaviors you care about including people, process, and outcomes. “Not everyone will win the Nobel Prize so we have a lot of ways to recognize excellence and people who demonstrate the right behaviors,” said Dr. Robert (Bob) Mahley, MD, PhD. who led Gladstone for its first 30 years. Awards can be for being a great mentor or mentee, research excellence and career advancement among others. Notably, there is also an Award for Team Excellence to recognize and reward cross-functional teams.

Giving people public credit for their contributions to a team effort always matters, especially in research. A recent game-changing breakthrough in antivirals—a single-dose intranasal treatment for the SARS-CoV-2 virus—was published in the journal Cell in December 2021. Two lead authors are Gladstone Senior Investigator and Director of the Center for Cell Circuitry Leor Weinberger, PhD. and research investigator, Sonali Chaturvedi, PhD. in the Gladstone Institute of Virology, including eight other researchers from Gladstone as well as many others outside of Gladstone.

2. Form cross-disciplinary teams early and often

Cross-disciplinary collaboration is central to Gladstone’s vision and has paid off repeatedly. “Gladstone saw early on the power of mining the growing mountains of global genetic data to understand, detect and treat disease,” said Dr. Deepak Srivastava, president of Gladstone Institutes and a pediatric cardiologist studying genetics and regeneration. A new domain of expertise was needed to master this mountain of data. Pollard, renowned for her work in bioinformatics, was hired to bring “Big Data” genomic analytics to Gladstone.

“To generate, analyze and interpret a large amount of data, you need computer scientists who can speak biology. Deriving meaning from data requires collaboration of biology researchers and data scientists who understand the research and scientific method. Early in the process of discovery, identifying targeted hypotheses to test can be as important as finding the “answers” especially since causes and answers are rarely singular.” Deepak Srivastava, President Gladstone Institutes.

Intense up-front collaboration between the team in Pollard’s lab and Gladstone experimental scientists has revealed promising avenues for research and treatment. Having data scientists sit down with biologists at the beginning of the research instead of the end helps to identify how to ask the questions so that Big Data and new statistical methods can be applied to existing data sets and the new data that will be collected.

Pollard’s team has cleverly applied picture recognition software, famously used on the web to identify cats and people, to 2-D pictures of folded chromosomes. Have enough of these pictures, point deep-learning algorithms at them and what emerges are patterns in the “white spaces” that may be the root of genetic diseases, such as congenital heart defects that can’t be explained by genes or epigenetic patterns alone. Pollard’s team and Gladstone biologists now hypothesize that, when a chromosome is folded and tucked inside a cell nucleus, the spaces between now-adjacent strands of the tightly packed chromosome, now visible “statistically” can be blocked or unblocked. This can, in turn, affect the expression of a gene and lead to disease. This novel use of picture recognition opens a whole new avenue for detection and potentially treatment of disease.

Data analytics and computational analysis is also helping Gladstone researchers identify existing drugs, already FDA approved, that could be repurposed to treat other diseases. By investigating huge existing databases Dr. Yadong Huang and his collaborators discovered that a commonly used diuretic for treating hypertension, bumetanide, reverses signs of Alzheimer’s disease in mice and in human cells and is highly correlated with reduced chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease in population studies. The beauty of repurposing existing drugs is that they come already FDA approved and ready to be pressed into service quickly.

As anyone who has conducted a survey knows, you need to know what you are trying to learn and how you will analyze the data before you create the data collection instrument. “My team and I wouldn’t consider launching into a research project without a deep dive into data analysis first,” avowed Dr. Ott.

This collaborative handshake extends beyond the boundaries of Gladstone. Seeking research funds is often an exhausting zero-sum game, with various institutions competing for finite grant monies. For example, for the bumetanide finding Dr. Huang and his team collaborated with UC San Francisco and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Gladstone continues to join forces with other like-minded institutions to seek funding for multi-institution research projects, including innovative approaches to eliminating HIV in Ott’s lab.

3. Orchestrate Serendipity

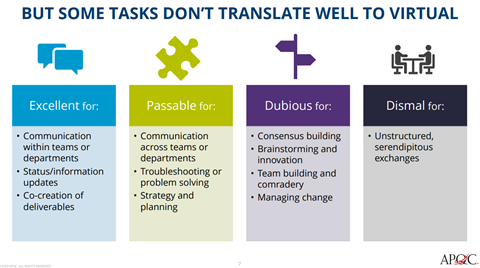

Finally, co-location still matters. A recent APQC survey with over 800 respondents found that while some tasks are fine for virtual, some don’t translate well at all. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1 (Source: Take virtual collaboration to the next level (apqc.org)

Virtual collaboration, whether via Zoom or Microsoft Teams, is poor for brainstorming and innovation and dismal for unstructured, serendipitous exchanges.

During my recent visit to Gladstone, I was getting a cup of coffee from a fancy coffee machine in the entry lobby furnished with soft, inviting, and now-empty seating. Weinberger, unknown to me at the time, wheeled in his bike to get coffee. We were introduced and I asked him what he was working on when his co-author Sonali Chaturvedi also showed up. That’s when I found out about their promising intranasal treatment to combat any variant of the COVID-19 virus.

Today, Gladstone leaders face the same challenges as other organizations in balancing safety with the need for chance encounters, awhile providing places people can talk in relaxed settings and see what magic emerges. They are trying to orchestrate more encounters like mine with Weinberger and Chaturvedi.

So how do we orchestrate serendipity and create a sense of community in a COVID-endemic world? First, we need to decide the reasons behind physical presence in the office. “It makes no sense to come into the office and spend your day in Zoom meetings” sighed Dr. Srivastava who had spent the morning doing just that.

Gladstone is exploring the option of building a new multistory building adjacent to the current facilities. This offers an opportunity to design for “the New Reality.” One idea is to create “landing platforms” on stairways complete with comfortable seating, coffee machines and food. (You can reliably attract people with coffee and food.) This will encourage people from different floors to interact.

Second, decide what norms to establish for safely spending time together. Other organizations are proposing holding lectures with wide appeal in open spaces. Cross-department group lunches and team events to keep people engaged and give them reasons to come in need to be part of the solution.

Gladstone Institutes’ experience makes a strong argument for using these three approaches—hire and reward collaborative people, form cross-disciplinary teams early and often, and orchestrate serendipity—to strengthen your organization’s collaborative muscle and produce better outcomes.