In my last blog I identified the first step in improving a cross-functional process at your organization: using the Process Classification Framework to standardize the listing of all of the steps and activities used by each business or operational silo.

This month’s blog is focused on providing practical and tactical advice to help you overcome this obstacle in your process journey.

Do you know who is going to set that new single standard? Who will approve business rules that enable acceptable variation? Who will approve/reject suggested improvements to the process over time, and communicate those changes to all relevant players? Do you even know who the “relevant players” are?

Until governance issues are resolved, progress will be limited.

Take Me To Your Leader...

Who owns each of the cross-functional processes at your organization – the big, end-to-end tasks that cut across multiple business units, functions or offices? If you can answer that question, you have my permission to take the rest of the day off – you’re way ahead of the game.

If you’re not packing up your things just yet, don’t worry ... you’re not alone. When organizations haven’t intentionally managed cross-functionally, processes tend to grow organically in functional and business silos. So, when an organization first decides to start managing cross-functionally, a governance crisis is almost inevitable. (The crisis usually presents itself as either a cross-functional processes without an owner, or worse, multiple owners.)

Step One: Quantify Your Governance Challenge

The key starting questions are: Do we have a single end-to-end owner of this process? Do we have several? Who thinks they own what pieces of the process? And, the hardest question of them all: How do you know?

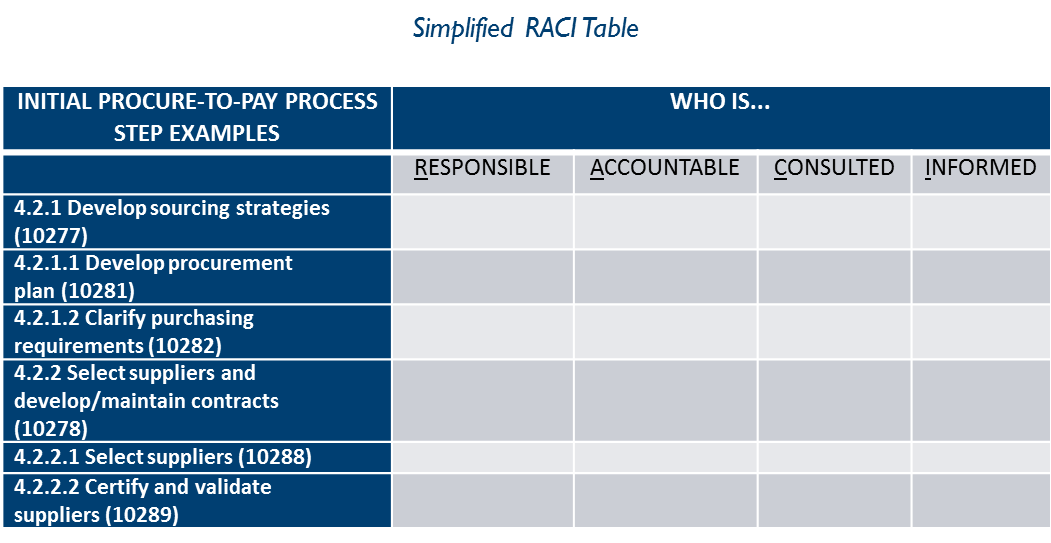

The fastest way to begin identifying the relevant players in a process is to build a RACI chart, a simple table used to identify who are Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed (RACI) about each task in a process. And then work with each business unit/silo to help fill in the chart.

Expect to discover that you have different or multiple responsible people or “R”s identified by each silo. Power abhors a vacuum. Unless a single owner had previously been assigned, it’s likely that multiple people have stepped up to try to run the process. And when the process flow moves from one function to another (i.e., in “Procure-to-Pay”, at some point the process is thrown over the wall from purchasing to finance), you’ll also likely see that you currently have different perceptions on who is responsible for the process.

In addition to the “R”s, capture all of those who are accountable (the professionals who actually execute the process), those that need to be consulted (those who work in adjacent processes, both upstream and downstream) and those that needs to be informed of changes (those that don’t necessarily have any say in those changes, but need to be kept in the loop).

While our focus at this point is on the “R”s, it’s crucial from a buy-in or change management perspective to capture everyone that even tangentially touches the process. The last thing you want is someone to be left out. You’ll have enough headaches sorting out power struggles without also being distracted by hurt feelings.

Step Two: Acknowledge and Address Power Struggles

Having multiple owners of a process is problematic. The role of a process owner, at a minimum, is to approve changes or improvements to a process and then communicate those changes. What happens if one co-owner makes a unilateral change without the consent of the other co-owner(s)? What if all co-owners are not aware of a change? The risk is a return to the lack of standardization that you had before. Or worse, total chaos and a breakdown of goodwill that’s necessary to implement your eventual changes.

What can you do? Like with any problem, the first step is acknowledging the issue exists. And the concern here is that someone has to gain power and someone else is going to lose power. Power can mean spending authority, resource prioritization, promotion, or higher salary. Don’t expect anyone to be willing to give up any of those for the greater good.

Instead of counting on altruism, consider one or more of the following:

Option 1: Rely on a senior executive to pick sides. Only someone with more power than the competing co-owners has the authority and credibility to make that call.

Option 2: Look holistically. Maybe the person losing power may be gaining power as another end-to-end process is consolidated.

Option 3: Détente. Work out a mutual agreement that while only one person can “own” the process, they will confer with the other prior co-owners. An ownership rotation every few years is also utilized at best-practice organizations.

Option 4: If all else fails, create an over-arching governance board to resolve any disagreements between co-owners. This will slow down your rate of progress, but failure to manage overlapping ownership can undermine your process improvements before they even have a chance to start.

Next Steps:

Once you have a single process owner in place to identify a single enterprise standard, you’re done ... right? Nope, but you’re off to a good start. Next month we’ll focus on the next biggest challenge facing organizations: Identifying what they don’t know about their processes.

Comments/Questions

If you have any questions or comments about your processes you’d rather not post publicly, please don’t hesitate to reach out to our Process Advisory team directly.

Jess Scheer can be reached by

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 1+ 713-685-7215